ESA Space Debris Environment Report 2022

Since 2016, ESA has published its annual Space Environment Report to provide a transparent overview of global space activities and determine how well international space debris mitigation measures and new technologies are improving the long-term sustainability of spaceflight.

The 2022 Report is now available.

According to the report, the first years of this decade have marked a new era for spaceflight. More satellites were launched into orbit in 2021 than ever before, up from last year’s previous record. Many of these satellites form part of large commercial constellations used to provide communication services around the globe. They offer new services, but will pose a challenge to long-term sustainability.

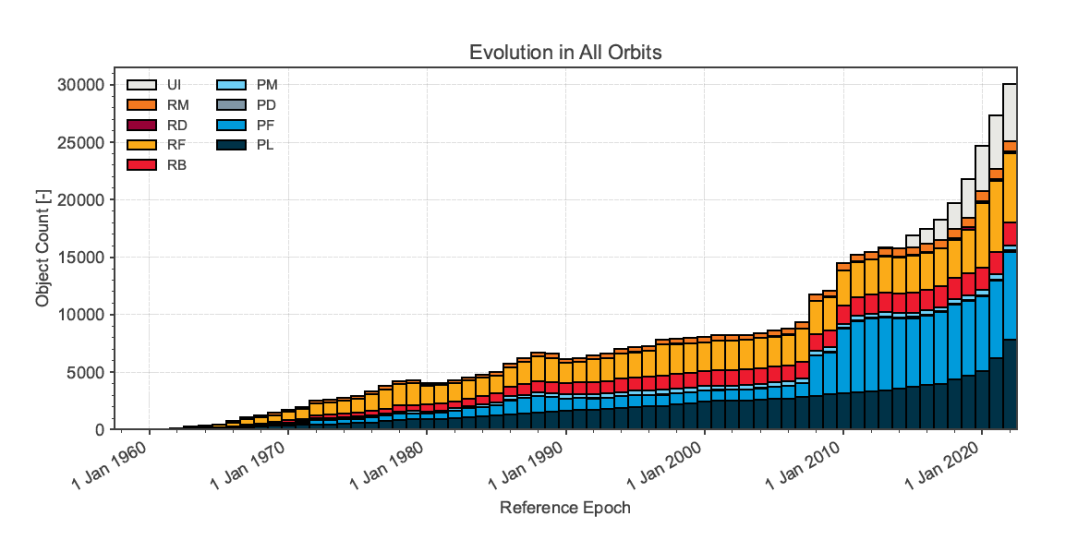

Meanwhile, the number of tracked debris objects in orbit has risen to more than 30 000. While many rocket bodies are removed from the busiest orbital highways after delivering their payload into orbit, not enough of these payloads are themselves safely removed at the end of their mission.

While global adherence to space debris mitigation guidelines is improving, there is still lots of work to be done to make our behaviour in space sustainable. Below are three key technologies that ESA and its partners are working on to ensure humankind’s continued access to valuable and limited low-Earth orbits and improve the outlook in next year’s report.

Space debris surveillance

More than 30 000 pieces of space debris are now regularly tracked by space surveillance networks.

While our current activity in space contributes to the rising number of tracked objects, new and improved technologies on the ground are allowing us to spot and survey more and increasingly small pieces of ‘unidentified’ (UI) space debris originally produced during unknown collisions or fragmentations years ago.

ESA’s IZN-1 laser ranging station is a technology testbed for the laser ranging of satellites and space debris, and a vital first step in making this new method of tracking small debris objects widely accessible to all space actors.

The station uses short laser pulses to determine the distance, velocity and orbit of satellites and space objects with millimetre precision, using the time the laser pulses take to return to the station. This millimetre precision could reduce the number of false alarms and unnecessary collision avoidance manoeuvres, saving valuable spacecraft fuel and engineer time on the ground.

In-orbit collision avoidance

As we launch more satellites into space and create more long-lasting space debris in low-Earth orbit, spacecraft are facing an increasing number of close encounters, known as conjunctions, with other objects.

In 2021, the average satellite at lower altitudes encountered another object over 40 times – mostly satellites that are part of large constellations providing commercial services. At higher altitudes, the average satellite more often encountered pieces of debris produced by a small number of famous and significant fragmentation events that occurred years ago.

Not all of these conjunction alerts require evasive action. But as the number of alerts increases, it will become impossible for spacecraft operators to respond to them all manually. Together with its industrial partners, ESA is developing automated systems that use artificial intelligence and other technologies such as signals from Galileo navigational satellites to help operators carry out these collision avoidance manoeuvres and reduce the number of false alarms.

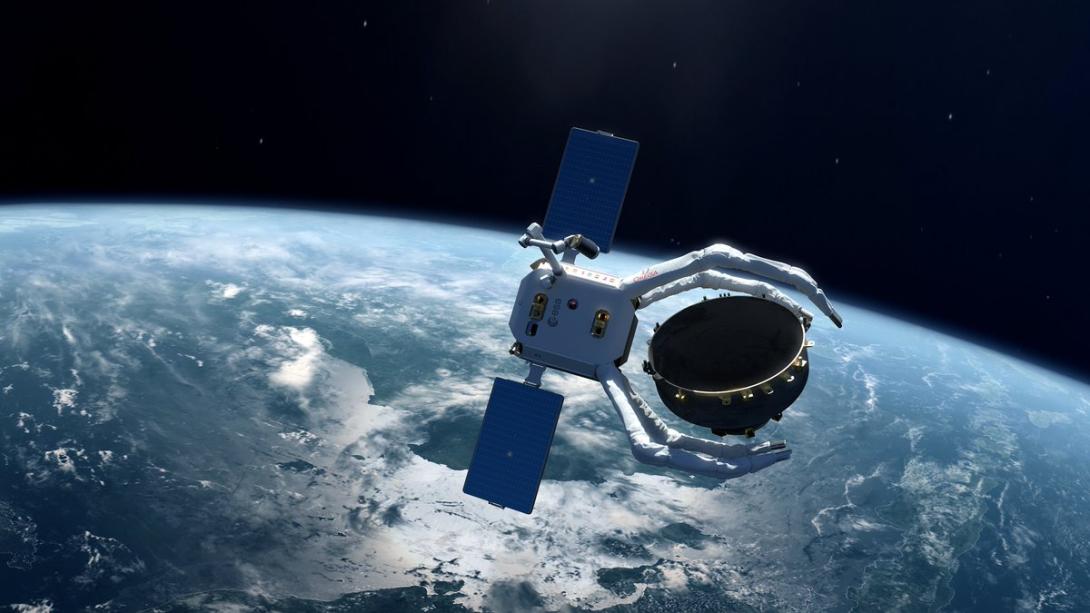

Active debris removal

The most effective way to slow the growth rate of space debris is to ensure at least 90 % of new objects we launch are removed from busy orbital highways at the end of their mission. But what do we do about the objects that are already in orbit and will remain there for a long time?

In April 2022, mission operators at ESOC had to perform a collision avoidance manoeuvre to keep the Copernicus Sentinel-1A Earth observation satellite safe from a possible collision with a fragment of a rocket launched 30 years ago. We need to start actively clearing larger objects from busy regions before they can break apart into debris that threatens spacecraft even decades later.

ClearSpace-1 will be the first mission to remove a piece of space debris from orbit. The spacecraft will rendezvous with, capture and safely bring down a 112 kg defunct rocket part, launched in 2013, for a safe atmospheric reentry.

ESA is purchasing the mission as a service from the Swiss start-up ‘Clearspace SA’ to demonstrate the technologies needed for active debris removal and as a first step to establishing a new and sustainable commercial sector in space dedicated to removing high-risk objects from our valuable and limited orbital highways.

It's time to act

Find out more about how effectively the world is responding to the space debris situation in ESA’s 2022 Space Environment Report.

Find out more about the steps ESA is taking to protect satellites in the essential orbits we use to study our changing climate, deliver global communication and navigation services and help us answer important scientific questions in the ‘Time to Act’ video.